Reverse-engineering an AC IR remote protocol

My new house has a Kelon-branded air-conditioning unit. Wouldn’t it be nice to have it set up in openHAB? I looked it up online and this unheard of brand’s protocol is nowhere to be found. So I had to figure it out myself.

I reverse engineered its protocol and contributed it to IRremote-ESP8266.

In this post I’d like to document my experience and what I learned from it.

Note

Since when this article was published, the code for the snippets shown has changed in the actual library code.

The changes are not particularly dramatic, therefore I decided to leave the snippets as they are, since my goal is to show my learning process, not perfect code (not implying that the final result is perfect - you get what I mean, I hope).

If you’re interested in the actual fully-working and properly tested code, check out the actual library source code.

First steps

Mi Remote app

As a former user of a Xiaomi phone equipped with an IR sender LED, I am aware of the Mi Remote application. It always surprised me how it seems to support literally every IR remote on Earth, I haven’t yet stumbled upon a device that isn’t supported.

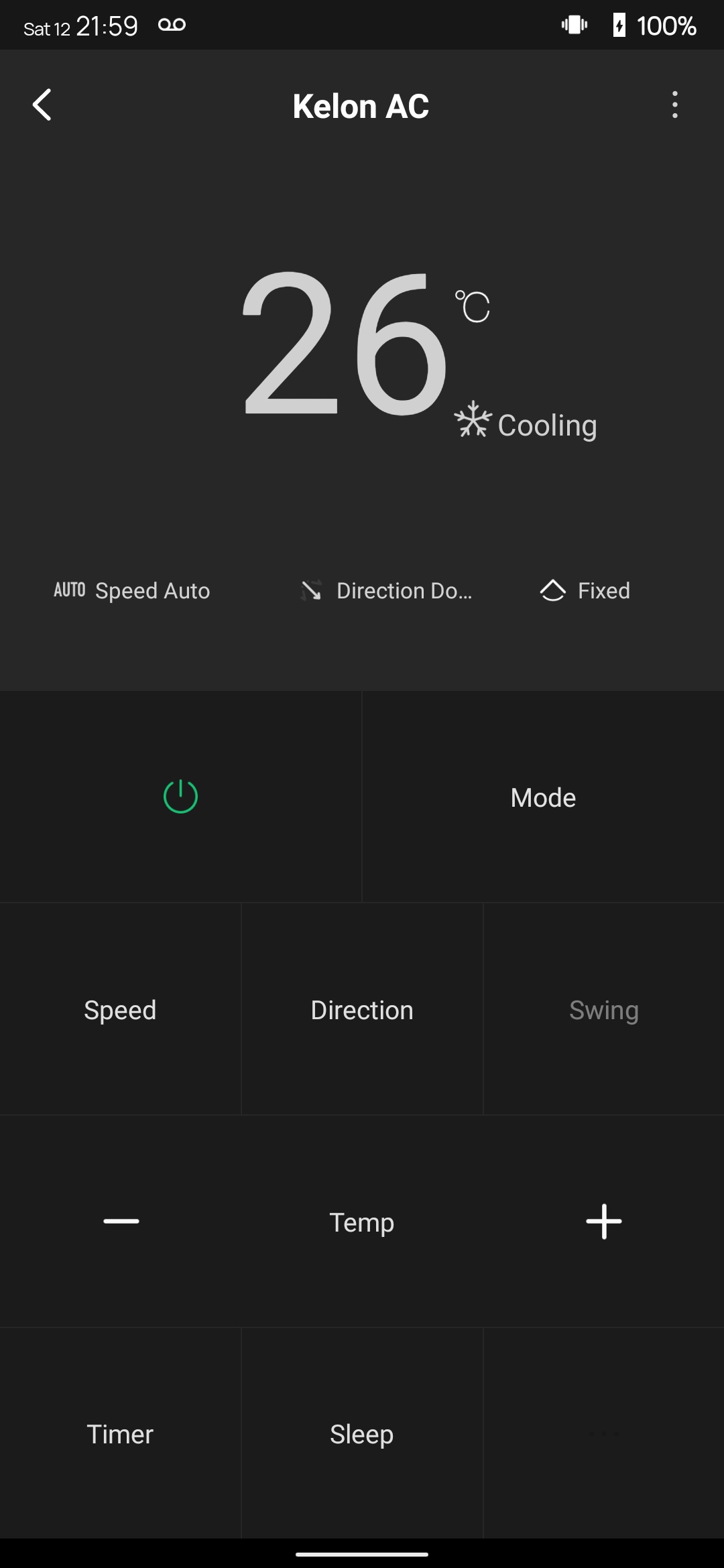

So I pulled out my old phone and, sure enough, “Kelon AC” was supported.

Since I didn’t know a lot about IR remotes yet, but I do know about software reverse engineering, I figured I could dump the application’s private files from my rooted phone and see if there’s anything interesting.

Sure enough, /data/data/com.duokan.phone.remotecontroller/databases/ir_data is a SQLite3 database:

$ sqlite3 ir_data

SQLite version 3.35.5 2021-04-19 18:32:05

Enter ".help" for usage hints.

sqlite> .tables

android_metadata mydevice

sqlite> .schema mydevice

CREATE TABLE mydevice(id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY, name varchar(20) not null, type INTEGER, version INTEGER, addDate DATETIME, lastmodify DATETIME, origin varchar(20), info varchar(20), lastUse varchar(20), stickytime INTEGER);

sqlite> select * from mydevice;

# ... lots of stuff

sqlite> select origin from mydevice where id=5;

{

"encoding": "UTF-8",

"language": "en",

"data": {

"_id": "kk_3_92_11797",

"frequency": "38000",

"key": {

"300": "9000,4500",

"301": "560,560",

"302": "560,1680",

"1001": "00020204",

"1002": "06830600020000",

"1011": "000003181C0003181C0103181C0203181C0303181C0403181C0503181C0603181C0703181C0803181C0903181C0A03181C0B03181C0C",

"1012": "031C2002031C2000031C2001031C2004031C2003",

"1505": "T|S&1,2,3",

"1504": "T|S&0",

"1013": "03161800031618030316180203161801",

"306": "1",

"305": "382",

"1501": "T&16,17",

"1502": "T&16,17",

"1503": "T",

"1517": "22@5&0-3*1",

"1515": "22|0-1|0|CHAD@09|0-600,30$660-1440,60|1|CHAFD@10|0-600,30$660-1440,60|0|CHAFD",

"1016": "04011516010407101101",

"1017": "051600141500@051601141501",

"1518": "if(exts~=nil) then\nif(power==1) then\ntiming_on=exts[9]; \nif((timing_on~=nil)and(timing_on>0) and (timing_on<=600))then\nbytes[4]=bytes[4]|0x08;\nbytes[5]=math.floor(timing_on\/30);\nelseif((timing_on~=nil)and(timing_on>600) and (timing_on<=1440))then \nbytes[4]=bytes[4]|0x08;\nbytes[5]=0x14 + (math.floor(timing_on-600)\/60);\nend\nelseif(power==0) then\ntiming_off=exts[10]; \nif((timing_off~=nil)and(timing_off>0) and (timing_off<=1440))then\nbytes[4]=bytes[4]|0x08;\nbytes[5]=math.floor(timing_off\/30);\nelseif((timing_off~=nil)and(timing_off>600) and (timing_off<=600))then\nbytes[4]=bytes[4]|0x08;\nbytes[5]=0x14 + (math.floor(timing_off-600)\/60);\nend\nend\nend",

"1506": "1",

"888888": [

{

"fid": 9,

"fkey": "timing_on",

"fname": ""

},

{

"fid": 10,

"fkey": "timing_off",

"fname": ""

},

{

"fid": 22,

"fkey": "sleep",

"fname": ""

}

]

},

"version": 1004,

"ext_flag": true

},

"status": 0

}

If I open up JadX and look around I can find the meaning of some of those opaque numeric JSON keys:

300: Lead code

301: Zero code

302: One code

305: Code format

306: Little-endian

1001: Power 1

1002: Code template

1501: Cooling mode

1502: Heating mode

1503: Auto mode

1504: Fan-only mode

1505: Drying mode

1506: Up-down swing mode

1515: Key format map

1517: Key cancel config

1518: Lua script for complex functionality

888888: Custom keys for Lua script

Cool, now what do I do with this info? Well, as it turns out, nothing.

I kept looking around at the decompiled code in JadX and I was able to figure out some more info about the format, but it was taking too long.

However, some useful info does stand out:

"frequency": "38000",

"key": {

"300": "9000,4500", # Lead code

"301": "560,560", # Zero code

"302": "560,1680", # One code

"306": "1", # Little-endian

# ...

}

This will turn out to be very useful later.

Reverse engineering the remote

Since reversing the app didn’t prove to be extremely useful and it was taking me way too long than I anticipated, I decided to instead try to decode and reverse-engineer the codes from the remote itself.

So I looked up online for some IR remote library capable of decoding and I found IRremote-ESP8266 (which also works with ESP32). I decided to give it a shot since I was going to use an ESP32/ESP8266 anyway for the final controller board.

I flashed the dumper example to my ESP32 and connected a IR remote receiver. I pressed keys and I got this:

### Power button

Timestamp : 000030.953

Library : v2.7.18

Protocol : UNKNOWN

Code : 0x6795432F (50 Bits)

uint16_t rawData[99] = {9034, 4508, 568, 1672, 570, 1674, 480, 668, 568, 592, 568, 594, 568, 594, 568, 590, 458, 1746, 568, 620, 544, 1652, 568, 1674, 568, 596, 568, 592, 568, 616, 544, 594, 568, 596, 568, 590, 570, 594, 566, 592, 568, 590, 570, 592, 568, 594, 566, 592, 570, 596, 568, 592, 570, 1678, 566, 592, 568, 592, 568, 1674, 570, 1672, 568, 1674, 568, 594, 568, 590, 568, 594, 568, 590, 568, 592, 568, 590, 568, 594, 568, 592, 568, 596, 568, 594, 568, 594, 568, 592, 570, 596, 568, 592, 568, 590, 568, 594, 568, 592, 568}; // UNKNOWN 6795432F

### Temp 26°C → 25°C

Timestamp : 000033.622

Library : v2.7.18

Protocol : UNKNOWN

Code : 0xA065EFDF (50 Bits)

uint16_t rawData[99] = {9032, 4508, 568, 1678, 566, 1674, 568, 592, 568, 592, 568, 592, 568, 590, 568, 594, 568, 1672, 568, 592, 568, 1674, 500, 1708, 568, 594, 568, 570, 568, 592, 568, 594, 568, 592, 570, 594, 568, 574, 468, 606, 568, 592, 568, 594, 568, 616, 544, 594, 568, 592, 568, 590, 568, 1676, 568, 592, 568, 590, 570, 590, 568, 1674, 568, 1672, 570, 592, 568, 592, 568, 592, 568, 592, 568, 594, 570, 592, 570, 594, 568, 592, 568, 594, 568, 592, 568, 594, 568, 594, 570, 590, 568, 592, 570, 592, 568, 592, 570, 590, 570}; // UNKNOWN A065EFDF

### Temp 25°C → 24°C

Timestamp : 000034.343

Library : v2.7.18

Protocol : UNKNOWN

Code : 0x726B6355 (50 Bits)

uint16_t rawData[99] = {9034, 4504, 570, 1672, 570, 1674, 568, 592, 568, 592, 568, 590, 568, 622, 544, 596, 568, 1674, 568, 592, 568, 1652, 570, 1676, 568, 590, 570, 590, 570, 592, 568, 596, 568, 620, 544, 592, 570, 592, 568, 1676, 568, 594, 570, 592, 568, 592, 570, 592, 568, 592, 568, 594, 568, 1672, 568, 618, 544, 596, 568, 596, 568, 592, 568, 592, 570, 1676, 568, 592, 568, 592, 568, 594, 568, 592, 568, 596, 568, 592, 568, 590, 570, 592, 568, 590, 570, 590, 568, 590, 570, 590, 570, 616, 544, 594, 568, 592, 568, 592, 568}; // UNKNOWN 726B6355

That UNKNOWN isn’t something I’d call reassuring, but then I thought maybe the code it is showing makes sense.

It turns out it doesn’t. I tried sending it back using an IR LED and nothing happened on the remote.

On top of that I can tell that something is wrong by just looking at the values. I already knew that most AC remotes send the entire set of settings at every button press. This may sound weird at first but it is actually a good idea since, if it only sent button presses like TV remotes, the remote could easily de-sync from the AC unit and show wrong info on the display.

With that being said, all the actions involve changing exclusively one setting (power, temperature), therefore I would expect only one or two bits to change at a time, and maybe a checksum. However, in the values I got the entire code changed at each button press.

This could also mean that the code is encrypted, but I never considered this option since it is highly unlikely for an AC remote.

I had to dig deeper.

Bringing out the big guns

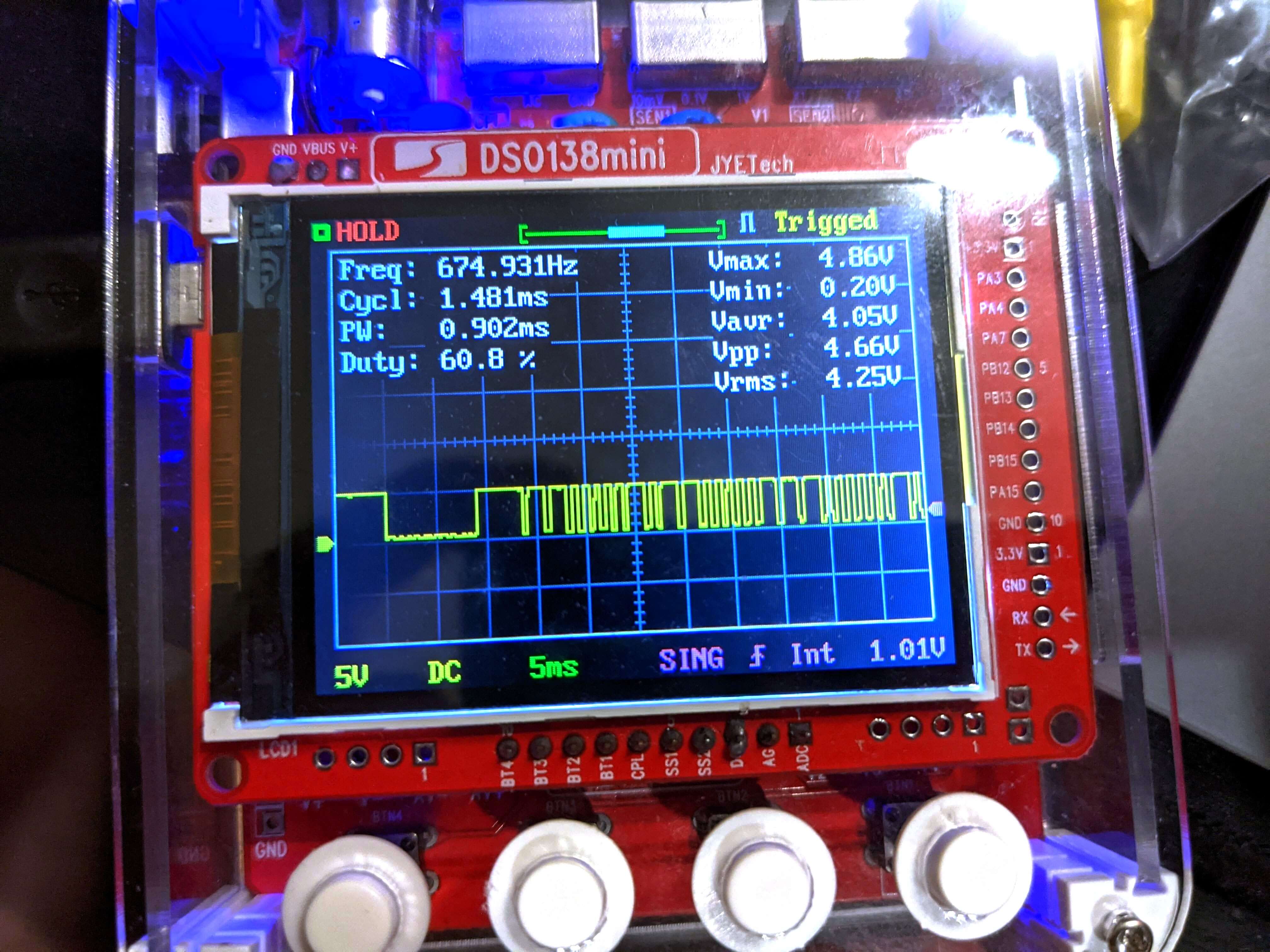

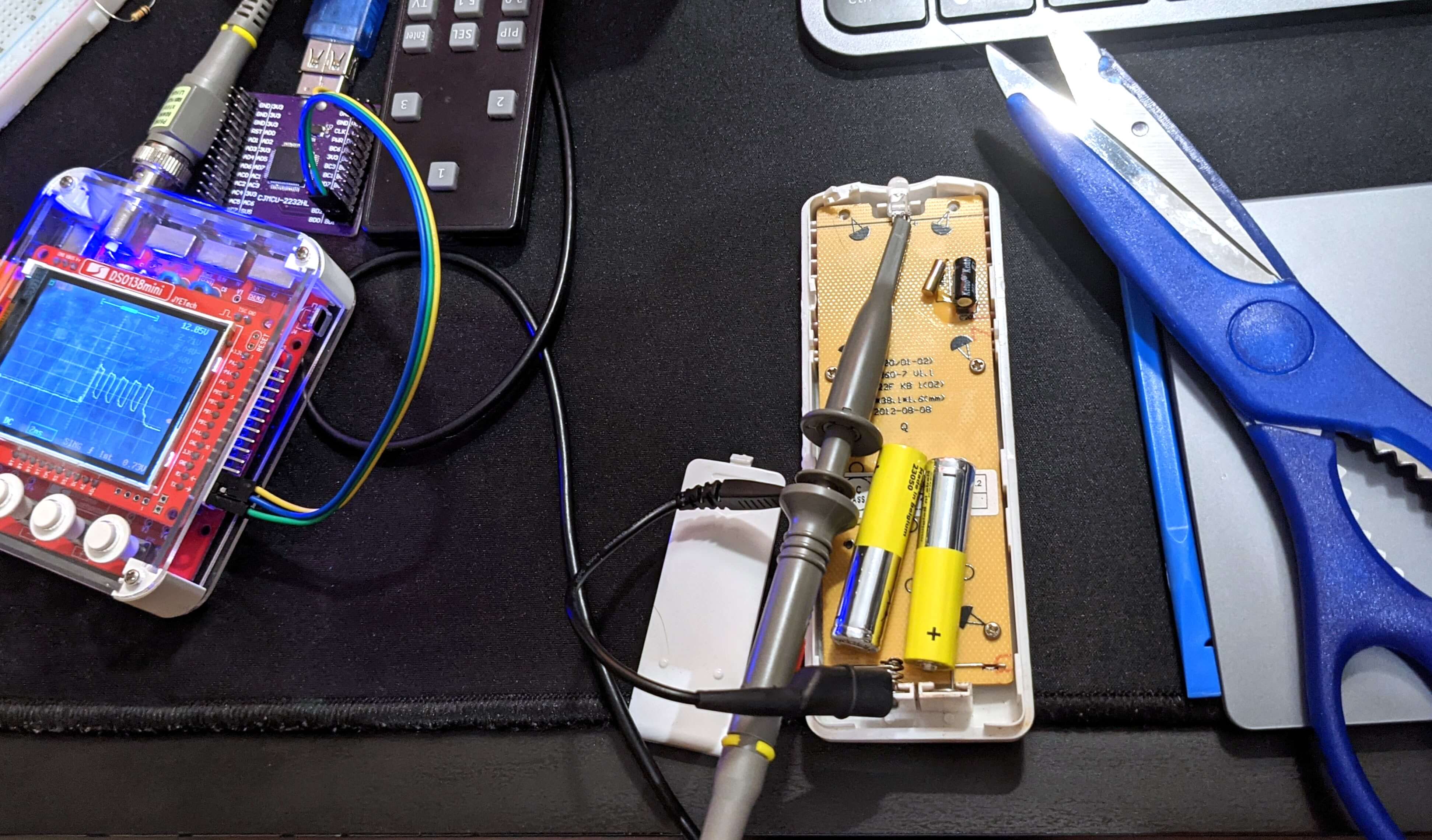

My DSO138mini portable oscilloscope

The picture you see is my portable oscilloscope from AliExpress. I connected it to the signal output of the IR receiver and that’s what I got.

That looked interesting, I thought this was a good way to proceed. However, trying to figure out stuff from a waveform on a whopping 2.7” display isn’t the best experience.

So, since the device supports sending waveform data over UART, I wrote a simple viewer for the format in Python, which you can find here on my GitHub.

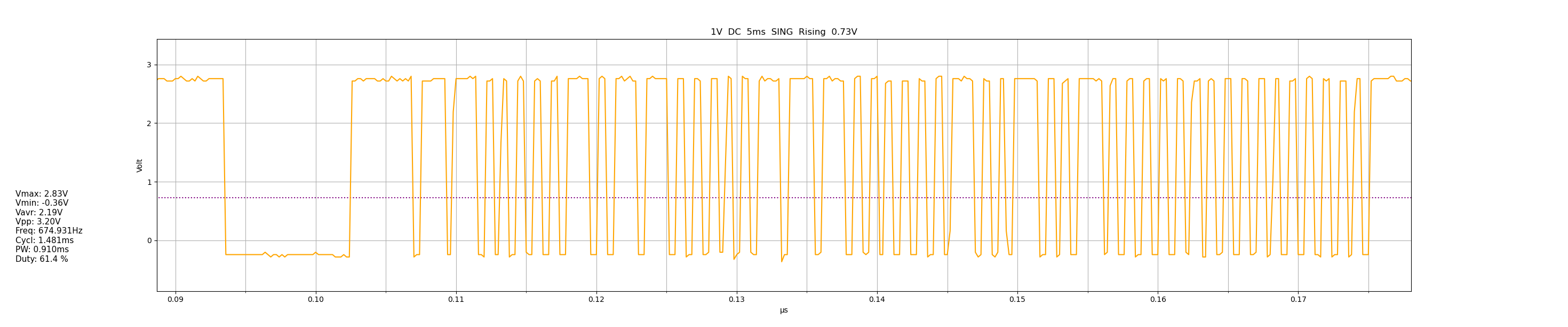

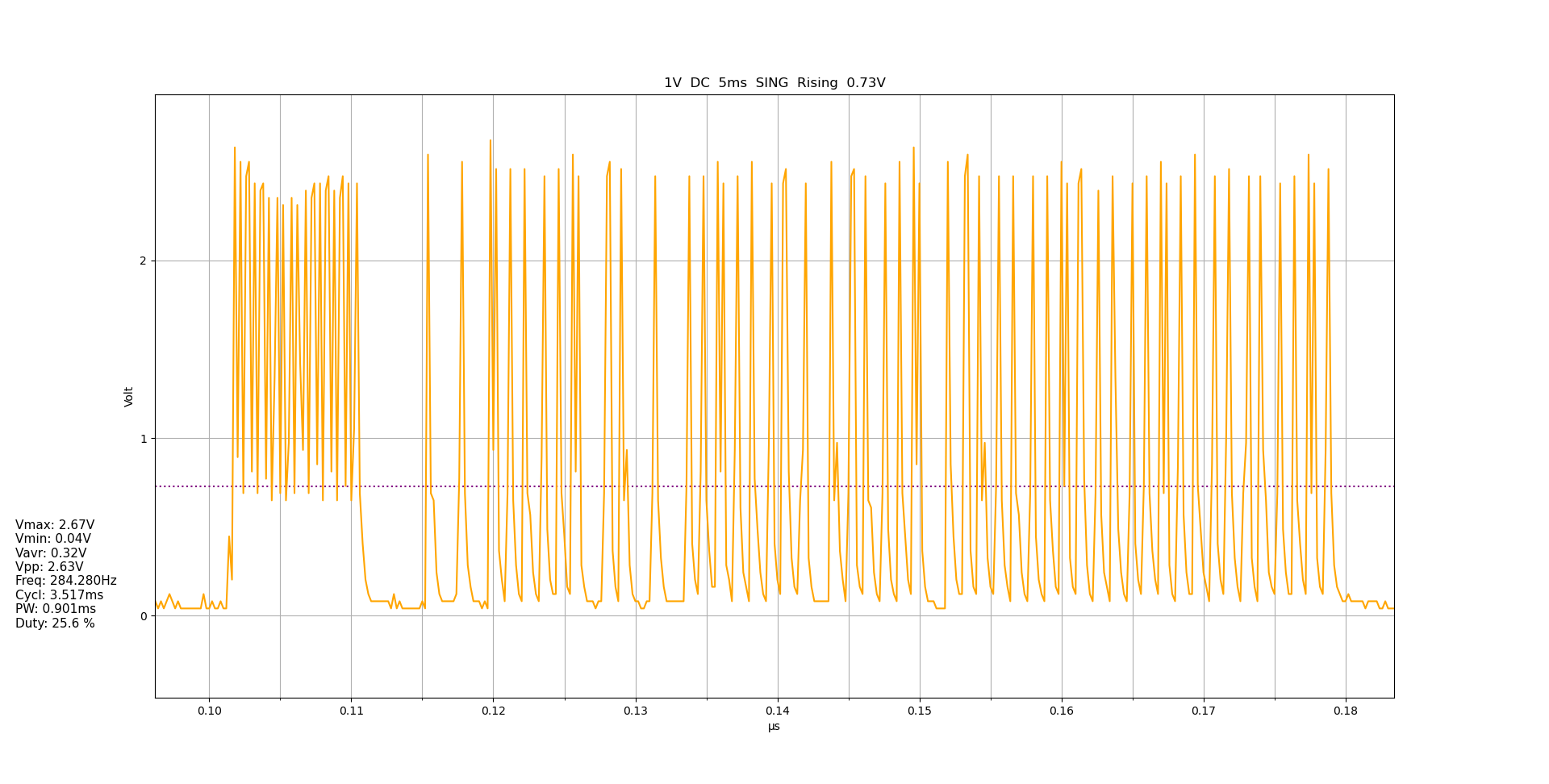

Waveform of the “power toggle” command

That’s a lot better.

So, after doing more research and looking at the waveforms from my scope, I learned that IR remotes:

- Send a sequence of signals

- The data is encoded into the timings of each signal

- Most remotes send a “header” with different timings to tell the receiver “hey I’m sending stuff”

- The length (in time) of each combination of “signal + no signal” section encodes each bit

- Some remotes also send a “footer” which often is just a single regular bit code

With this information I counted in the waveform the number of all “⨆⎺” sections: 49 in total, + the first big one which looks suspiciously like a header.

I then looked back the IRremote library output and, sure enough, it’s detecting 50 bits! (it’s probably considering the header as a bit).

Code : 0x6795432F (50 Bits)

uint16_t rawData[99] = {9034, 4508, 568, 1672, 570, 1674, 480, 668, 568, 592, 568, 594, 568, 594, 568, 590, 458, 1746, 568, 620, 544, 1652, 568, 1674, 568, 596, 568, 592, 568, 616, 544, 594, 568, 596, 568, 590, 570, 594, 566, 592, 568, 590, 570, 592, 568, 594, 566, 592, 570, 596, 568, 592, 570, 1678, 566, 592, 568, 592, 568, 1674, 570, 1672, 568, 1674, 568, 594, 568, 590, 568, 594, 568, 590, 568, 592, 568, 590, 568, 594, 568, 592, 568, 596, 568, 594, 568, 594, 568, 592, 570, 596, 568, 592, 568, 590, 568, 594, 568, 592, 568}; // UNKNOWN 6795432F

At this point I also looked at the rawData part of the IRremote output. Those numbers look familiar, remember this?

"frequency": "38000",

"key": {

"300": "9000,4500", # Lead code

"301": "560,560", # Zero code

"302": "560,1680", # One code

"306": "1", # Little-endian

# ...

}

Also, since 6 x 8 == 48, I can suspect that it’s actually sending 6 bytes, and that the very last reading is the footer.

The pieces of the puzzle are slowly coming together:

| Signal | No signal | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| ~9000 | ~4500 | Header |

| ~560 | ~590 (close enough to MiRemote) | Zero bit |

| ~560 | ~1680 | One bit |

| ~560 | forever | Footer |

I don’t know yet if the unit of these timing values is microseconds, potatoes or whatever (it turns out they are microseconds) but, looking at the waveform from earlier, the width gap after the very first signal is exactly twice as big as the width of the first signal.

So it looks like the values I got from the app code actually make sense!

Let’s decode it

Next step: I added a new IR remote implementation to IRremote-ESP8266 and tried to write a simple decoder for it:

const uint16_t kKelonHdrMark = 9000;

const uint16_t kKelonHdrSpace = 4600;

const uint16_t kKelonBitMark = 560;

const uint16_t kKelonOneSpace = 1680;

const uint16_t kKelonZeroSpace = 600;

const uint32_t kKelonGap = kDefaultMessageGap;

const uint16_t kKelonFreq = 38000;

bool IRrecv::decodeKelon(decode_results *results, uint16_t offset,

const uint16_t nbits, const bool strict) {

if (strict && nbits != kKelonBits) {

return false;

}

uint16_t used;

used = matchGeneric(results->rawbuf + offset, results->state,

results->rawlen - offset, nbits,

kKelonHdrMark, kKelonHdrSpace,

kKelonBitMark, kKelonOneSpace,

kKelonBitMark, kKelonZeroSpace,

kKelonBitMark, 0, false,

_tolerance, 0, false);

if (strict && used != nbits * 2 + 3) {

return false;

}

results->decode_type = decode_type_t::KELON;

results->bits = nbits;

return true;

}

Note: This is just the most relevant snippet. It turns out that the library is quite complicated, I actually had to make changes all over the place.

And, sure enough:

### Power button

Timestamp : 000022.412

Library : v2.7.18

Protocol : KELON

Code : 0x82040683 (48 Bits)

uint16_t rawData[99] = {8986, 4530, 546, 1698, 544, 1700, 544, 618, 544, 640, 520, 614, 546, 616, 544, 616, 546, 1698, 544, 614, 544, 1696, 546, 1696, 546, 616, 546, 618, 542, 616, 544, 618, 544, 616, 546, 616, 544, 576, 544, 1696, 546, 614, 544, 618, 546, 616, 544, 616, 544, 642, 520, 614, 546, 1696, 546, 616, 542, 620, 544, 616, 546, 616, 544, 618, 544, 1698, 544, 620, 544, 614, 544, 618, 544, 616, 542, 614, 546, 614, 544, 614, 546, 616, 544, 616, 544, 614, 544, 616, 544, 614, 544, 616, 544, 614, 546, 614, 544, 616, 546}; // KELON 82040683

uint64_t data = 0x82040683;

### Temp 26°C → 25°C

Timestamp : 000025.200

Library : v2.7.18

Protocol : KELON

Code : 0x72000683 (48 Bits)

uint16_t rawData[99] = {9010, 4528, 546, 1696, 546, 1698, 544, 572, 490, 608, 546, 616, 544, 616, 544, 616, 546, 1698, 544, 614, 546, 1696, 546, 1698, 546, 614, 546, 616, 544, 616, 544, 614, 546, 616, 544, 616, 546, 618, 544, 612, 548, 616, 544, 616, 544, 616, 550, 616, 542, 614, 546, 612, 546, 1696, 546, 616, 546, 616, 544, 1696, 546, 1698, 460, 1770, 520, 616, 544, 600, 544, 614, 546, 616, 544, 616, 544, 616, 546, 578, 544, 614, 544, 616, 544, 616, 544, 614, 548, 576, 546, 616, 544, 616, 542, 616, 546, 618, 544, 578, 544}; // KELON 72000683

uint64_t data = 0x72000683;

### Temp 25°C → 24°C

Timestamp : 000026.654

Library : v2.7.18

Protocol : KELON

Code : 0x62000683 (48 Bits)

uint16_t rawData[99] = {9010, 4528, 544, 1698, 546, 1696, 544, 618, 544, 618, 544, 616, 544, 618, 544, 614, 546, 1696, 546, 614, 546, 1680, 544, 1696, 546, 614, 544, 618, 544, 614, 546, 618, 544, 616, 544, 614, 546, 614, 546, 616, 544, 614, 544, 618, 544, 618, 544, 616, 544, 616, 544, 614, 546, 1698, 544, 616, 544, 616, 544, 638, 520, 1698, 544, 1700, 544, 614, 544, 618, 542, 614, 544, 614, 546, 614, 544, 616, 546, 618, 544, 618, 544, 616, 542, 614, 546, 618, 544, 616, 546, 616, 544, 616, 546, 616, 544, 614, 546, 618, 544}; // KELON 62000683

uint64_t data = 0x62000683;

Now only a few bits change at every button press, so that looks correct.

I then proceeded to add a similar sendKelon() method:

void IRsend::sendKelon(const uint64_t data, const uint16_t nbits, const uint16_t repeat) {

sendGeneric(kKelonHdrMark, kKelonHdrSpace,

kKelonBitMark, kKelonOneSpace,

kKelonBitMark, kKelonZeroSpace,

kKelonBitMark, kKelonGap,

data, nbits, kKelonFreq, false, // LSB First.

repeat, 50);

}

Except it didn’t work.

Bringing out even bigger guns

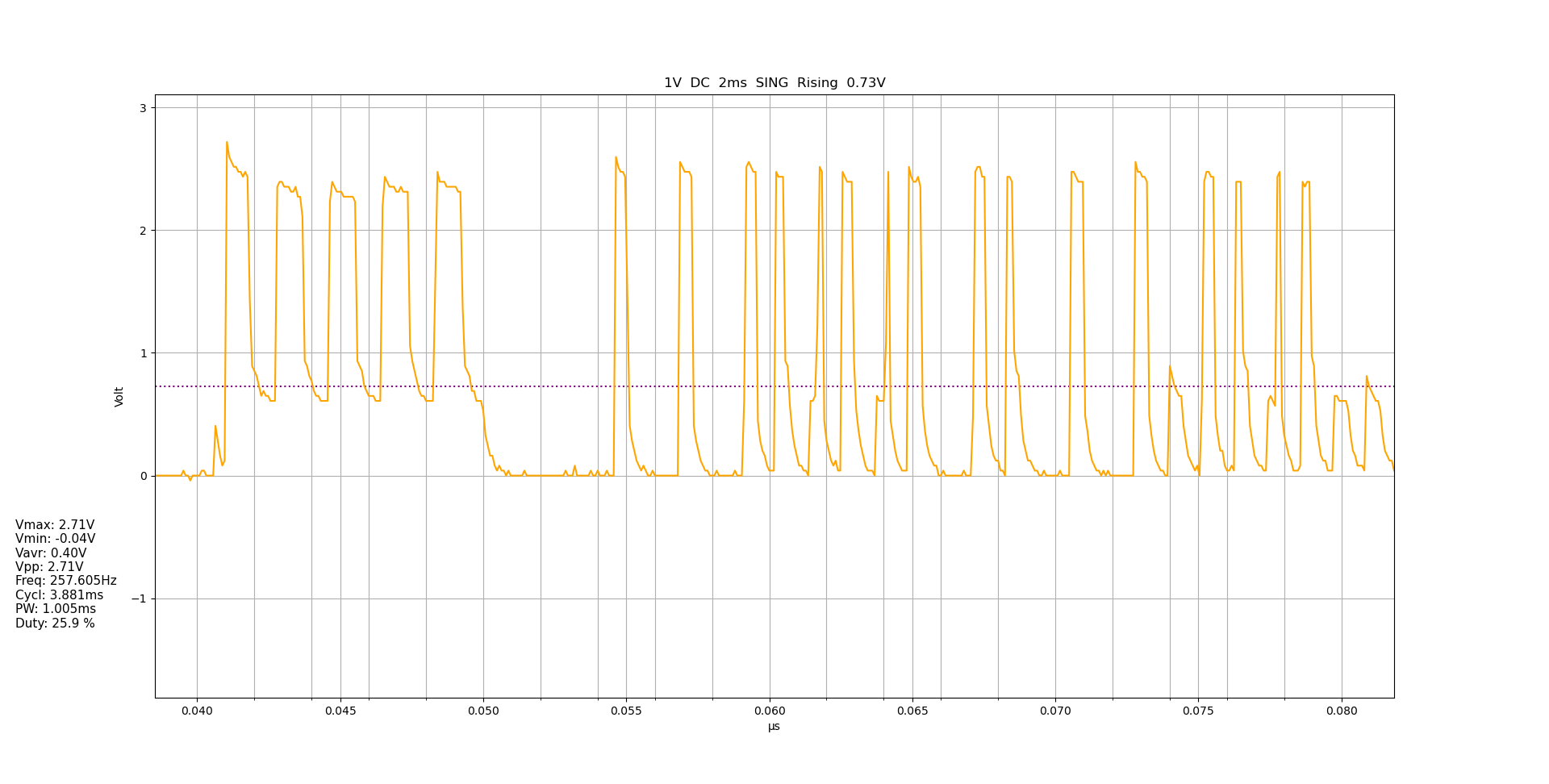

I wired up the scope once again, but this time I connected it to the IR LED on my breadboard to see what was going on.

I got something like this.

Waveform from the IR LED sending the “toggle power” command

This looks quite different from what I captured from the IR receiver.

To investigate this, I decided that, since the AC remote is my primary source of information, I should probably take it apart and measure from there. So that’s what I did.

I used the scissors to close the circuit on the two AAA batteries

I got a very similar waveform.

Waveform from the IR LED of the remote. Zoomed out ~50%

So, there must be something that I’m missing. And indeed, in the data from the Mi Remote app I can see this line:

"frequency": "38000"

It turns out that transmitting IR signals is slightly more complex than receiving it. In order to prevent false triggers from household infrared sources (like the sun, lighting, candles, humans) IR remotes actually send PWM signals.

The most common frequency is 38 kHz, with a duty cycle of 50%. When the receiver outputs a continuous signal, the IR LED is actually blinking at 38 kHz.

The receiver implements a band-pass filter, filtering out everything but signals at around 38 kHz.

My issues with sending turned out to be a simple wiring issue… whoops! My code actually worked fine.

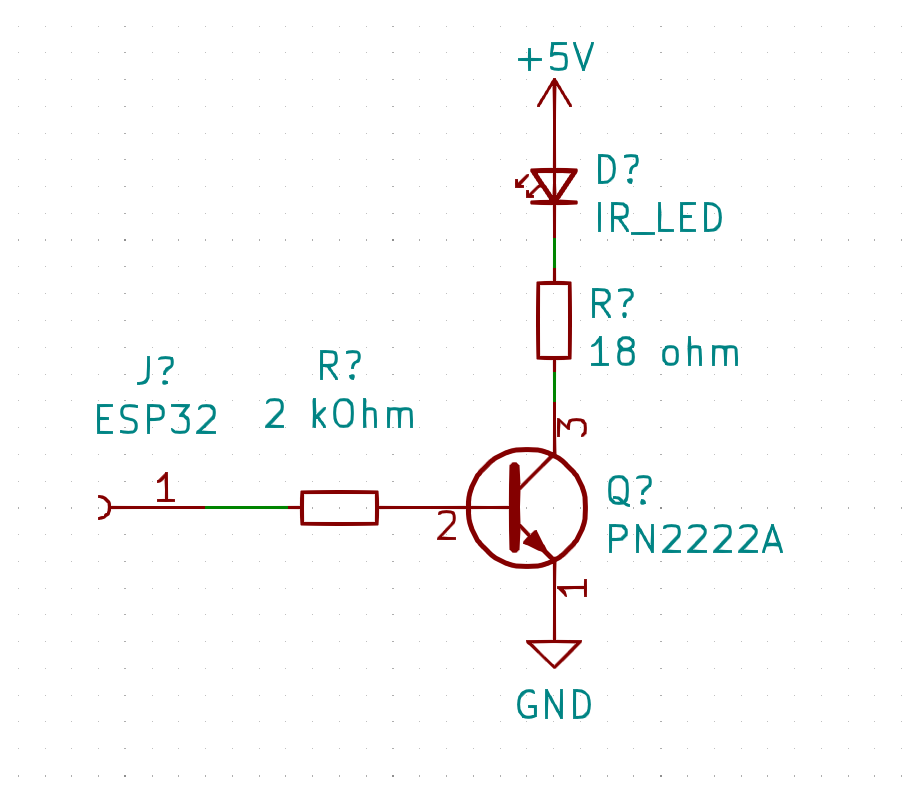

It seems to work a lot more reliably when driven by a transistor, like this:

Understanding the IR codes

Once the decoding is working I can ahead, press all the buttons and try to figure out the code. So that’s what I did, I collected all the information in this table:

| Value | Temp | Fan | Mode | Timer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x82000683 | 26 | Auto | Cool | ||

| 0x72040683 | 25 | Auto | Cool | Power | |

| 0x72000683 | 25 | Auto | Cool | ||

| 0x72010683 | 25 | Max | Cool | ||

| 0x72020683 | 25 | Med | Cool | ||

| 0x72030683 | 25 | Min | Cool | ||

| 0x72800683 | 25 | Auto | Cool | Swing | |

| 0x73000683 | 22 | Auto | Dry | ||

| 0x73100683 | +1 | Auto | Dry | ||

| 0x73200683 | +2 | Max | Dry | ||

| 0x73500683 | -1 | Med | Dry | ||

| 0x73600683 | -2 | Min | Dry | ||

| 0x74010683 | – | Max | Fan | ||

| 0x50000683 | 23 | Auto | Warm | ||

| 0x60000683 | 24 | Auto | Warm | ||

| 0x820B0683 | 26 | Min | Cool | Sleep | |

| 0x900002010683 | 18 | Max | Cool | Super | |

| 0x8081000683 | – | Auto | – | Smart | |

| 0x19A000683 | – | – | – | 0.5h | |

| 0x28A000683 | – | – | – | 1h | |

| 0x78A000683 | – | – | – | 3.5h | |

| 0xC8A000683 | – | – | – | 6h | |

| 0x138A000683 | – | – | – | 9.5h | |

| 0x168A000683 | – | – | – | 12h | |

| 0x228A000683 | – | – | – | 24h |

Hexadecimal values are quite hard to analyze, so I converted them to binary, aligned them and analyzed them:

In [8]: for i in values:

...: print(f"{bin(i):>50} {hex(i):>14}")

...:

0b10000010000000000000011010000011 0x82000683

0b1110010000001000000011010000011 0x72040683

0b1110010000000000000011010000011 0x72000683

0b1110010000000010000011010000011 0x72010683

0b1110010000000100000011010000011 0x72020683

0b1110010000000110000011010000011 0x72030683

0b1110010100000000000011010000011 0x72800683

0b1110011000000000000011010000011 0x73000683

0b1110011000100000000011010000011 0x73100683

0b1110011001000000000011010000011 0x73200683

0b1110011010100000000011010000011 0x73500683

0b1110011011000000000011010000011 0x73600683

0b1110100000000010000011010000011 0x74010683

0b1010000000000000000011010000011 0x50000683

0b1100000000000000000011010000011 0x60000683

0b10000010000010110000011010000011 0x820b0683

0b100100000000000000000010000000010000011010000011 0x900002010683

0b1000000010000001000000000000011010000011 0x8081000683

0b110011010000000000000011010000011 0x19a000683

0b1010001010000000000000011010000011 0x28a000683

0b11110001010000000000000011010000011 0x78a000683

0b110010001010000000000000011010000011 0xc8a000683

0b1001110001010000000000000011010000011 0x138a000683

0b1011010001010000000000000011010000011 0x168a000683

0b10001010001010000000000000011010000011 0x228a000683

It looks like the first two bytes (least significant, so on the right) never change. We can strip them out, it must be some sort of preamble.

In [11]: for i in values:

...: print(f"{bin(i)[:-16]:>35} {hex(i):>14}")

...:

...:

...:

...:

0b1000001000000000 0x82000683

0b111001000000100 0x72040683

0b111001000000000 0x72000683

0b111001000000001 0x72010683

0b111001000000010 0x72020683

0b111001000000011 0x72030683

0b111001010000000 0x72800683

0b111001100000000 0x73000683

0b111001100010000 0x73100683

0b111001100100000 0x73200683

0b111001101010000 0x73500683

0b111001101100000 0x73600683

0b111010000000001 0x74010683

0b101000000000000 0x50000683

0b110000000000000 0x60000683

0b1000001000001011 0x820b0683

0b10010000000000000000001000000001 0x900002010683

0b100000001000000100000000 0x8081000683

0b11001101000000000 0x19a000683

0b101000101000000000 0x28a000683

0b1111000101000000000 0x78a000683

0b11001000101000000000 0xc8a000683

0b100111000101000000000 0x138a000683

0b101101000101000000000 0x168a000683

0b1000101000101000000000 0x228a000683

Much easier to read.

I took my time and carefully compared all the values to each other and to the table. This is the result:

MSB LSB

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0110 1000 0011 Preamble

XX Fan speed (0 auto, 1 max, 2 med, 3 min)

X Power toggle

X Sleep (1 == on)

XXX Dehumidifier intensity (signed)

X Swing toggle

XXX Mode (0 heat, 1 maybe smart, 2 cool, 3 dehum, 4 fan)

X Timer on

XXXX Temperature (0 == 18)

X Timer half hour *

XXX XXX Timer hours *

X Smart mode

?? ???? ? Unknown / Reserved ?

X X Super cool mode

* if timer hours > 10, timer hours is obtained by also considering the half hour bit in

the number, then subtracting 10

Figuring out the dehumidifier intensity and the timer setting was tricky: in the first case, they don’t use 2’s complement like normal people but instead just flip a bit for the negative sign. But that’s fine I guess.

For the timer, the remote doesn’t count the half hours past 10h. For the first 10h the last bit signals +30m. After that, for some reason, they use the entire 7 bits to encode the time but it’s offset by +10.

I mean, for 20h you send 30. WTF?

I then verified this information by writing a simple decoder script in Python. You can find it in this GitHub Gist.

$ ./kelon_decoder.py 0x228A000683

Fan speed: auto

Power: not pressed

Sleep: off

Dehum intensity: +0

Swing: not pressed

Mode: cool

Timer: on

Temperature: 26°C

Timer duration: 24h

Smart mode: off

Supercool mode: off

Is the AC on?

After doing all of this I realized one thing: the remote doesn’t tell the AC whether it should be on or off. It tells it whether the power button is pressed or not.

WTF.

This is not only stupid, since both behaviors take exactly the same amount of bits (that is, ONE), but it defeats my original purpose of setting it up in openHAB, which is what I use for my home automation.

I’d like to be able to use openHAB to set automation rules so that the AC automatically turns on while I’m coming back home, this plot twist breaks the entire purpose of this effort.

However, I found a workaround. I read the AC manual front to back and it turns out that setting it to “smart” or “supercool” mode always works, regardless of whether it is on or off. If it’s off, it will turn on.

That means I can do this very nasty thing:

void IRKelonAC::ensurePower(bool on) {

// Try to avoid turning on the compressor for this operation.

// "Dry grade", when in "smart" mode, acts as a temperature offset that

// the user can configure if they feel too cold or too hot. By setting

// it to +2 we're setting the temperature to ~28°C, which will

// effectively set the AC to fan mode.

int8_t previousDry = getDryGrade();

setDryGrade(2);

setMode(kKelonModeSmart);

send();

setDryGrade(previousDry);

setMode(_previousMode);

if (!on) {

// Now we're sure it's on. Turn it back off.

setTogglePower(true);

}

send();

}

End of this story

With all this done, all that remains is to contribute the code to IRremote-ESP8266. I won’t get into that since it’s simple, boring C++ programming.

I submitted a pull-request and, at the time of writing, it is being reviewed: crankyoldgit/IRremoteESP8266#1494

Update 2021-07-03: it is now merged 🎉.

Once that’s done I will be soldering a simple board on a perfboard to drive the LED, then write a firmware to control it over MQTT.

I also won’t get into that because once again it’s boring, but if you’re into making something like this you can look at this other firmware I wrote for a similar purpose in the past. Nothing too fancy :)

Thanks for reading!